The signs in front of the factories claim their adherence to labor laws and intolerance to child labor, but inside, the scenario is very different.

The textile industry in India, with an estimated value of 84 billion Euros, and a

supplier for dozens of clothing brands across India, Europe, America and Australia, relies secretly and heavily on child labor.

In spinning mills, dyeing plants and factories,

girls as young as eleven, vulnerable to physical and psychological abuse,

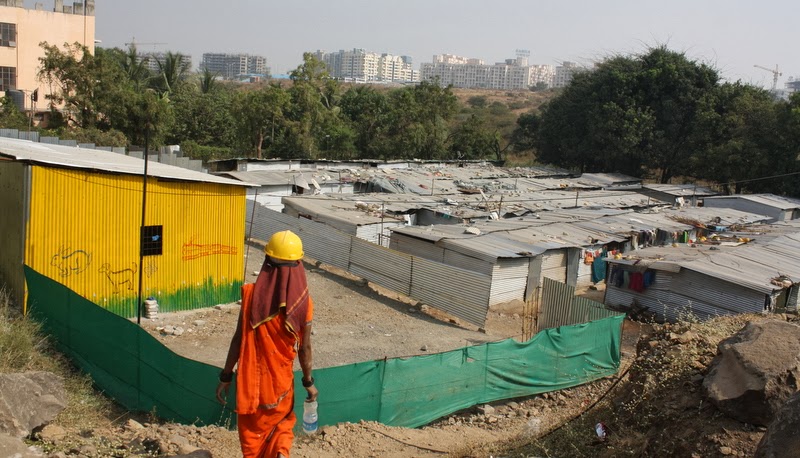

remain locked in residences during their period of service behind high walls and barbed wire.

The system is known as

Sumangali, which means “happily married” in Tamil language, and is offered to poor families

as a way for girls to earn enough money to pay their dowry. Rights activists estimate there could be around 200,000 girls associated with the system. The Indian government is aware of it, but

efforts to eradicate it have failed for lack of political will and the economic power of the sector.

In a village in Tamil Nadu, Rajeshwari plans, with the help of her grandmother, to rescue her sister from a cotton spinning mill. “I'll bring her home,” says the grandmother. “They have to release her, she's my granddaughter. She wanted to go, but now she feels very bad... long hours, low pay and bad living conditions.”

Rajeshwari knows it’s true because she spent a year and a half behind the walls of the same factory. At 14, her verbal contract was for three years, after which she was told she would get €470. While she was working, she made

€17 a month which went down to €11 if she missed a single day of work. She had to work overtime and was beaten if her production was not high enough.

“There were three shifts each day, so we had to do compulsory night shifts. I was very tired all the time and sometimes I didn’t even eat.”

After a year and a half, she could not take it anymore. Despite completing half of her service, she received no part of the promised amount. Rajeshwari has given up on the money and wants her sister back, but the situation is complicated because the agent who accepted the commission is a relative.

It is not only poverty that drives families to “sell” their daughters. In the heartland of ultraconservative Hindu Tamil Nadu, girls are kept away from society from puberty until marriage. If girls are isolated for three years, safe from harm as far as the parents can tell, and working to pay their dowry at the same time, a valuable social purpose is served.

Systems that make underage girls work in servitude violate numerous laws in India, but textile networks are economically and politically powerful. Many factories belong to politicians or their families, and the huge amounts of money the industry generates

are vital for the economy and livelihoods of millions of families.

This massive industry is complex and supply chains are deliberately kept secret so that

it is almost impossible for Western consumers to locate the origin of their clothes. The National Human Rights Commission of the government of India has ordered the government of Tamil Nadu to ensure that Sumangali and similar systems are abolished, but the industry hides behind the high walls of the factories.

A representative of Stop the Traffik says that these systems are “a modern form of slavery”, but adds that

boycotting countries with entire economies that depend on clothing manufacture is counterproductive. Instead, she says, consumers and

Western brands have to ensure that clothes are made ethically. “Right now you can’t make a perfect choice, but you can make a better choice,” she says. “The fashion industry is highly profitable for some. We are asking people to make changes that will make life better for the poorest of the poor.”

Source: smh.com